A is for AI… which has made coursebooks even less relevant.

In 2012, two months before I would venture across the Atlantic to Budapest from my home in upstate New York to take the CELTA course and enter the world of ELT, Scott Thornbury published a marvelous piece on his blog which would only become relevant and comprehensible to me four or five years later as I navigated my new role working as a corporate business English trainer in Germany.

Teaching in corporate training rooms for six or seven back to back sessions was a challenge that the CELTA had not prepared me for. I had small groups of professionals who had very specific reasons for learning English, a lot to talk about, and very little time to waste. And I had no time to waste on hours of lesson planning and making photocopies.

Around the time I discovered Dogme, which revolutionized my teaching, I found a blog post by Thornbury called E is for E Coursebook. It was both a call for not simply using new tech to do the same old things (publishing mass-market coursebooks which deliver “grammar McNuggets” and present dry, static texts, etc.) and a glimpse at how tech could be used to craft relevant and engaging language lessons spontaneously, based on what was actually going on with the actual people in the room. I was hooked.

Thornbury presented a quick possible sketch of how tech could be used to replace instead of to peddle published materials.

https://scottthornbury.wordpress.com/2012/01/29/e-is-for-ecoursebook/

- A topic arises naturally out of the initial classroom chat. The teacher searches for a YouTube video on that topic and screens it. The usual checks of understanding ensue, along with further discussion.

- A transcript of the video, or part of it, is generated using some kind of voice recognition software; alternatively, the learners work on a transcription together, and this is projected on to the interactive whiteboard, which is simply a whiteboard powered by an eBeam.

- A cloze test is automatically generated, which students complete.

- A word-list (and possibly a list of frequently occurring clusters) is generated from the text, using text processing tools such as those available at The Compleat Lexical Tutor. A keyword list is generated from the word list. Learners use the keywords to reconstruct the text – using pen and paper, or tablet computers.

- On the basis of the preceding task, problematic patterns or phrases are identified and further examples are retrieved using a phrase search tool.

- The target phrases are individually ‘personalised’ by the learners and then shared, by being projected on to the board and anonymised, the task being to guess who said what, leading to further discussion. Alternatively, the phrases are turned into questions to form the basis of a class survey, conducted as a milling activity, then collated and summarised, again on to the board.

- In small groups students blog a summary of the lesson.

- At the same time, the teacher uses online software to generate a quiz of some of the vocabulary that came up in the lesson, to finish off with.

Countless twists on the above have inspired my teaching ever since. Sometimes it’s an infographic or short text, sometimes a TED talk or YouTube video. Very often, just the language that emerges from discussion or tasks on a shared virtual whiteboard. And with a good grasp of digital tools virtual teaching, far from being bland and monotonous, became an immersive experience.

Enter OpenAI.

Last week, OpenAI released a beta version of their newest language processing model and it is currently free to use. The tool can do a stunning amount of language related tasks instantly. I began experimenting and I haven’t been able to stop since. So to pay homage to Scott’s 2012 post, and hopefully start a conversation with other teachers about applying this new technology, here is an example of how it can be used.

One example

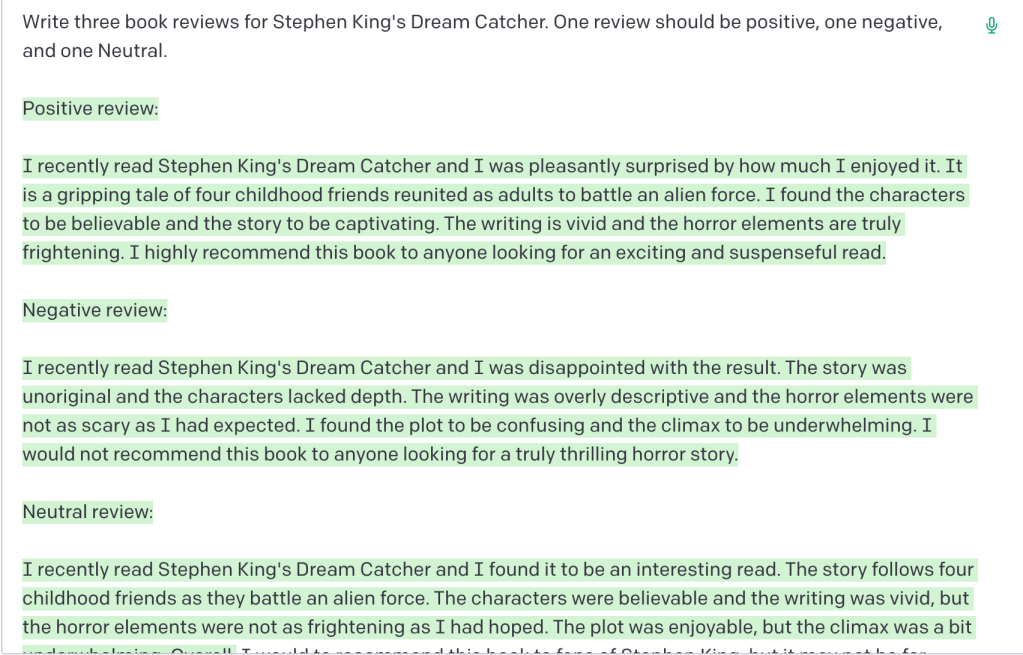

A B2 conversation class entered the (virtual) room and learners were immediately talking about books. After some chit chat, I asked about their favorite authors. One of them mentioned Stephen King, so I logged into the playground section of OpenAI and asked it to write me three book reviews of a Stephen King novel. It churned out the following within two seconds:

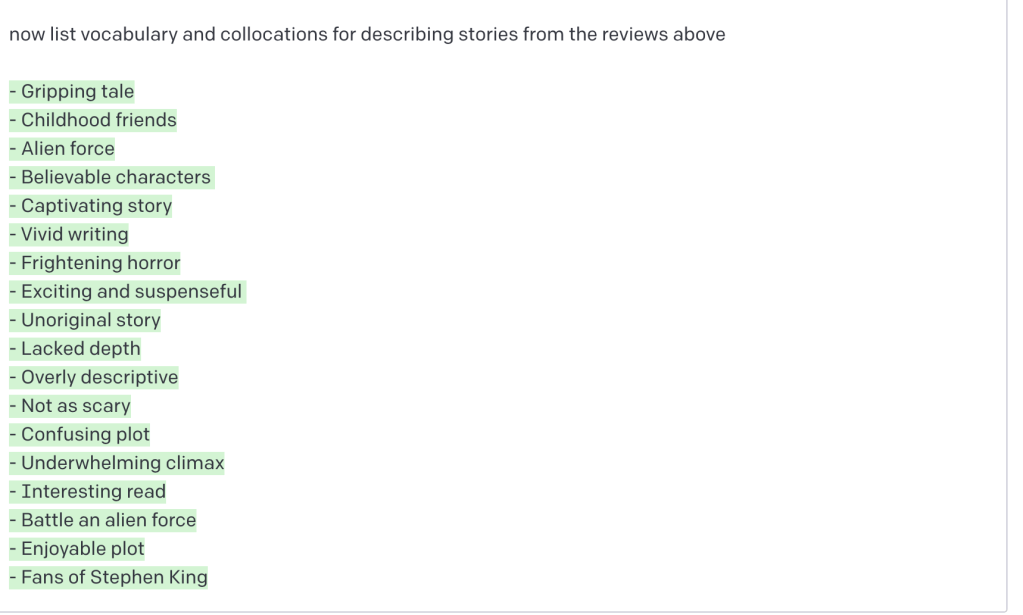

Then I prompted it to list all of the collocations that could be found in the text:

Brilliant. I started by displaying the list of collocations on a whiteboard. We went through the terms one by one, and I asked learners to decide if each one most likely belonged in a positive or negative book review…or if they were unable to tell.

Next, I displayed the three texts and they read them, deciding which review was positive, negative, or neutral, and why. Afterwards, they went through the texts again to highlight the terms we had already gone over, and to see if their initial guesses about which reviews the terms belonged in were right. Then, we went through the terms again and personalized them by discussing them with regards to their own experiences with books and reading.

After discussing a bunch of emergent language, learners went on to write their own short book reviews, encouraged, but not mandated, to use language we had already covered.

Just getting started

That is just one of countless examples of how this can be used in the language classroom. I’m inclined to think that the primary benefit is that it allows us to create compelling and level appropriate input and good models without needing to worry about copyright issues nor searching the web for texts for hours… though the interface will also rewrite texts for you and give you written feedback on texts. OpenAI will write in a variety of styles and will take pragmatics into consideration depending on the instructions you input. It will also explain grammar rules to you if you ask it to (another nail in the coffin wasting lots of classroom time explicating grammar rules). Below are some prompts similar to ones that I have used with impressive results. If you are interested in using this platform but don’t know where to start, you can use them as inspiration:

- write a summary of Matt Cutt’s TED talk

- write two more summaries of the talk, with two incorrect pieces of factual information missing from each

- write me a list of the top 20 most important accounting terms in English and use those terms in a text about accounting in 2022. Then, create a version where the terms are replaced with gaps.

- write me a list of eight true and two false sentences about Germany

- write me a chain of professional emails. Email one should be a customer complaining about….Email two should be a response from Mr Smith at…. email three…

mix up the order of the emails - according to author David Brooks, what are the advantages and disadvantages of older and younger employees

- write a dialogue of two people meeting in a cafe. Include a bit of small talk, a funny joke, and something surprising.

- write a 250 word text in CEFR B2 level English about the world cup. Create a list of common collocations from the text. Replace the first word in each collocation with a gap and provide a wordlist

- write me a story that ends with “so that’s how I got my nickname, “Turkey Lips.”

- write the steps of how to change a tire

- write me a script of a phone conversation between a…. include….

I really think the possibilities are endless here, and as always…principles before tools. I don’t think this kind of tech is anywhere near replacing the value of the genuine social context of the classroom or virtual classroom when it comes to language learning…but it can certainly save teachers a ton of time and provide us with comprehensible input that can easily be adapted into engaging tasks.

What do you think?

Leave a reply to scarlet_erg Cancel reply